As we look at the familiar coins in our pockets and purses, it’s funny to think that money was once the source of great debate and confusion.

50 years ago, as many of you may remember, Britain marked the move to decimalisation. Known as ‘D-Day’, it signalled the moment shillings and pence – not to mention guineas and half-crowns – were abandoned in favour of the shiny new coins we use today. And what a change it was!

The move to decimalisation was one of the biggest economic upheavals in history but it was also a long time coming.

As far back as 1847 Parliament had discussed changing the imperial system that had been in place since the time of King Henry II to a currency based on units of ten, implying such a system would be simpler.

Other nations around the world adopted decimal currency, but it would take until 1966 for the British government to announce we were finally joining the decimal club as part of then Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s vision for a ‘modern’ Britain.

To get the UK ready, the Decimal Currency Board sprang into action, gently introducing new 5p, 10p and fancy seven-sided 50p coins into circulation in advance to get us used to the new money.

As we tried to forget the mantra of ‘12 pence in a shilling and 20 shillings in a pound’ that had been drummed into us, public information films soothed and reassured, explaining that “thinking decimal” would only make our lives easier.

In reality, though, while we grasped the idea of 100 pennies in a pound, remembering how a sixpence was now worth 2.5p and a halfpenny was 0.2p and so on, tended to give us a real headache!

TV shows tried to help such as the daily BBC show Decimal Five and ITV’s possibly rather patronising Granny Gets the Point, where an elderly woman is taught how to use the new system by her grandson.

Even the much-loved performer Max Bygraves was roped in for moral support with the release of a surprisingly catchy song featuring chants of D-E-C-I-M-A-L-I-S-ation that soon rang out around football stadiums and school assembly halls across the country.

For all the encouragement, though, many people were still understandably suspicious of decimalisation.

Some argued the old coins were too ingrained in our British heritage to be lost while others insisted, with good intentions but in a somewhat condescending tone of voice, that the elderly and poor housewives in particular had no chance of ever understanding the new system.

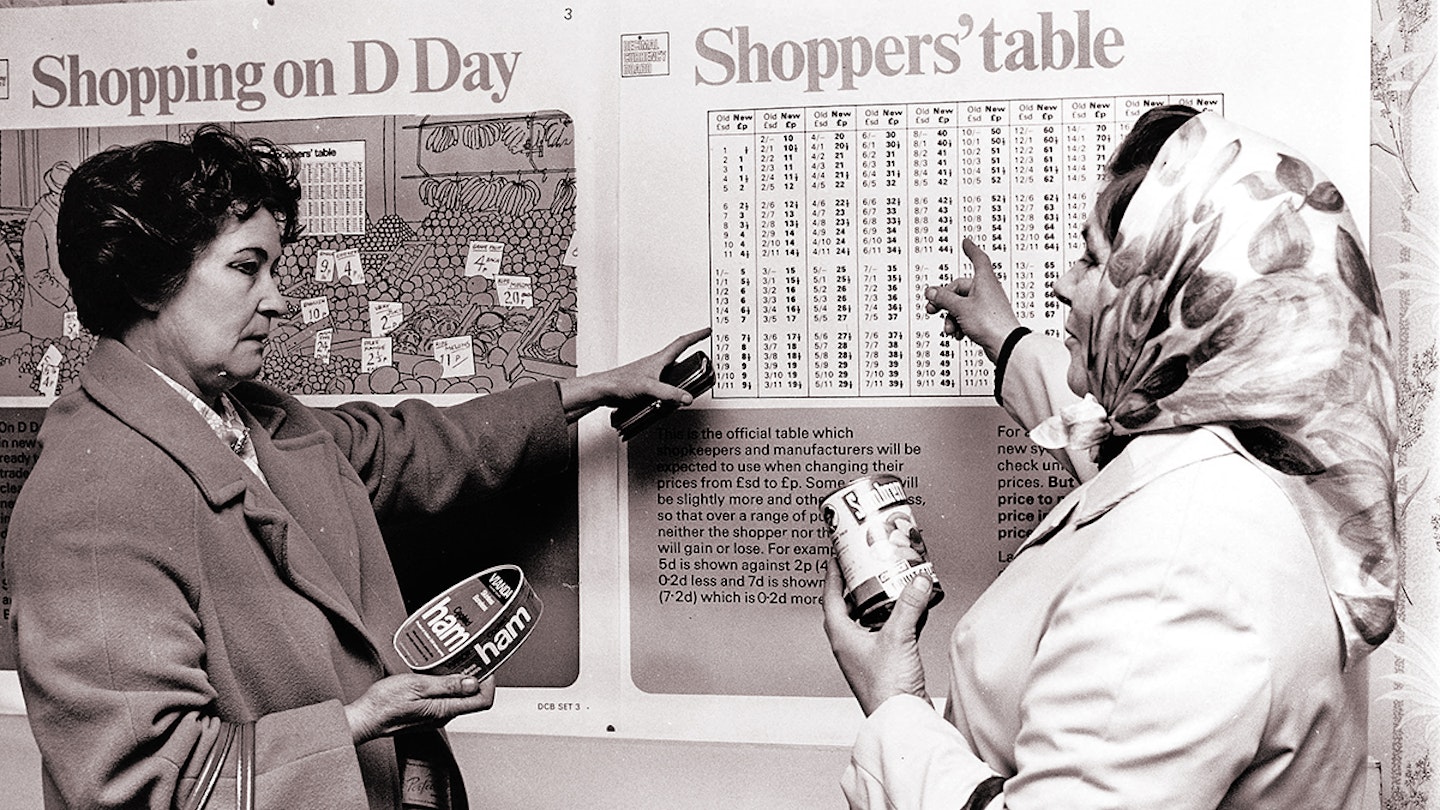

Another concern was that going decimal would allow sneaky shopkeepers the opportunity to hike their prices without anyone realising.

Nevertheless, for all the doubters, on February 15, 1971 – a date specifically chosen because it was thought to be a quiet period for banks and businesses – Britain went decimal, with the new 2p, 1p and ½p coins added into circulation.

In shops around the country there were currency converters and decimal adders to help work out the difference between old money and new.

Harrods even had an army of girls in boaters and blue sashes, known as ‘decimal pennies’, who were employed to help confused shoppers, while Selfridges did the same with girls dressed in what they called ‘suitably mathematically designed’ costumes.

Largely, Decimal Day went smoothly although there were a few hiccups that made the headlines from new coins jamming payphones to London libraries accused of profiteering from fines because of the change.

One of the most comical stories of the day, though, was how 50 Yorkshire children had been driven off to a police station after refusing to pay 5p for their bus fare, having worked out it should only be 3p in new money. In the end the children were proved correct all along.

For a short time after decimalisation, old and new currencies operated in tandem, meaning people could pay in pounds, shillings and pence and receive new money as change.

It had been planned that the old money would be phased out of circulation over 18 months, but things went so smoothly that the old penny, halfpenny and threepenny coins were taken out of circulation in August 1971 while the Decimal Currency Board did themselves out a job after just six months.

Thanks to public demand, the sixpence lasted until 1980 and the florin until 1993, while the ½p was abandoned in 1984 and the 20p introduced in 1982 along with the £1 coin in 1983. But in our increasingly cashless society, who can say what comes next?