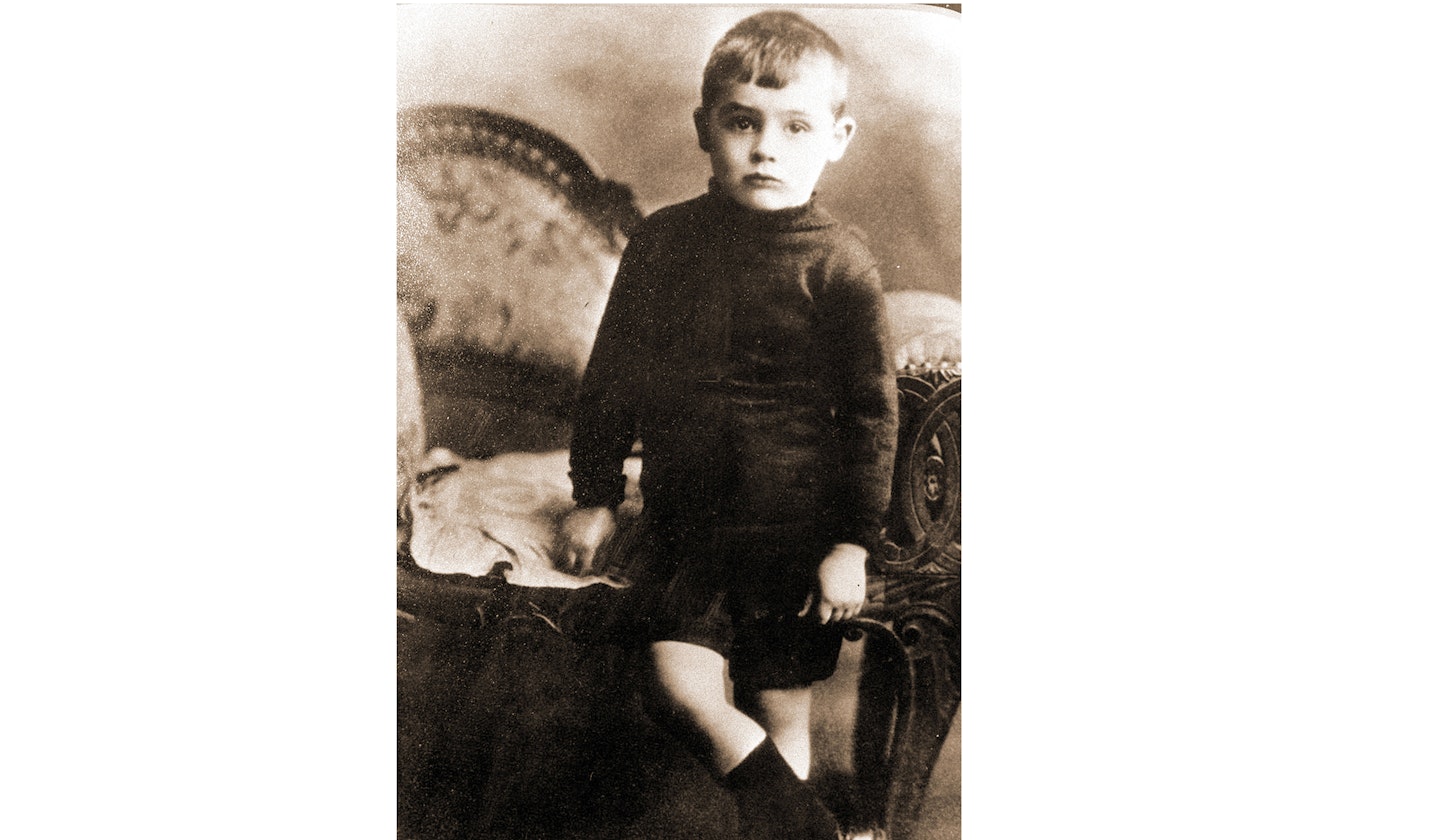

Born into a working-class family, Archibald Alexander Leach, known to you and I as Cary Grant, made the move to America when he was just 16 to pursue life as a big time Hollywood actor. Debonair, funny and poised, Grant never forgot where he came from and it was those humble beginnings that gave him the determination to succeed.

Elias and Elsie Leach raised their son well. Archie, born January 8, 1904, lived in a small stone house in Bristol. His parents took him to church, taught him to be polite to strangers, to have impeccable manners and be a stickler for the rules. He learned to speak only when spoken to and that money didn’t grow on trees.

More related articles: -The life and loves of Rita Hayworth -Diana Dors: life, love and fur bikinis! - Wallis Simpson: villain or victim?

Before Cary Grant was famous

In 1912 Elias Leach was offered a job in Southampton making uniforms for the expanding British army, and left the family in pursuit of more money. Although eight-year-old Archie missed his father he relished having his mother all to himself. But when his father returned a few months later there was obvious friction between the couple.

The following year Elsie disappeared – one day she was there squabbling with his father and the next she was gone. When Archie asked he was told she’d gone to a nearby resort for a rest. It wasn’t until many years later that he discovered the truth – she had suffered a nervous breakdown and been committed to a sanatorium for the mentally ill. Grant wouldn’t see his mother again for more than 20 years. About the meeting he said, “By that time I was a full-grown man living thousands of miles away in America. I was known to most people in the world by sight and by name, yet not to my mother.”

He speculated that her breakdown was triggered by guilt over the death of her first-born son. John Leach, born two years before Grant, had developed gangrene after a tragic accident. Elsie had cared for him diligently but through sheer exhaustion she had fallen asleep and during her nap the boy had died. Grant believed she never forgave herself.

Cary Grant's first taste of showbiz

With his father understandably distracted young Grant was left largely to his own devices. He didn’t enjoy school but was a hard-working student and won a scholarship to the local secondary school. But Grant was filled with a wanderlust. Eager to escape, he joined the Bristol YMCA Boy Scout Troup at the outbreak of the First World War and volunteered for air-raid duty (climbing up gas street lamps to extinguish them) and work as a messenger at Southampton docks.

It was at school though that Grant met a man that would change his life. A part-time lab assistant took him to see the newly refurbished Bristol Hippodrome. When they arrived the matinee show was in full-swing and Archie was blown away by what he saw. “When I arrived backstage I found myself in a dazzling land of smiling jostling people wearing all sorts of costumes and doing all sorts of clever things. And that’s when I knew. What other life could there be than that of an actor?”

From there Grant’s passion for all things theatrical just grew and grew. Aged 13 he helped with the lighting at the nearby Empire Theatre and started skipping school to spend more time there. Here he heard about Bob Pender’s troupe of comedy acrobats and cheekily wrote asking for work (forging his father’s signature). Bob sent the train fare and invited him to audition in Norwich. Grant intercepted the letter and set off, knowing it would be a while before his father spotted he was missing.

Pender agreed to take him on and Grant began learning acrobatics, tumbling and dance. But soon Elias turned up to reclaim his errant son insisting he return to finish his education.

Back in Bristol Grant set about trying to get himself expelled from school so he could re-join Pender’s troupe. Soon he achieved his goal and, realising he was fighting a losing battle, Elias handed him over to Pender. Within three months he was back in Bristol – but this time on stage at his beloved Empire theatre.

Later Grant said he regretted not finishing school but he was to have an education of a very different sort – an apprenticeship in the art of pantomime. He learnt how to convey emotion and meaning without words and impeccable comic timing – all of which would help make him the great actor he became.

Across the Atlantic

For two years the troupe toured the provinces but that excitement was soon eclipsed by a new adventure. Bob Pender booked to play in New York city and Grant was one of the eight boys chosen to go.

Grant made the most of his time in New York and when the tour ended he decided to stay in America and get work on his own. To make ends meet between theatre jobs he sold ties out of a suitcase and was a stilt walker at Coney Island.

He spent the next few years touring the US with various vaudeville troupes until a part on Broadway opposite Fay Wray earned him his first screen test. The talent scout was unimpressed saying, “he is bowlegged and his neck is too thick”. But that didn’t diminish Grant’s ambition. In November 1931 he drove to California determined to make it in the movies.

Soon he was signed to a contract with Paramount pictures who insisted the name Archie Leach had to go and Cary Grant was born.

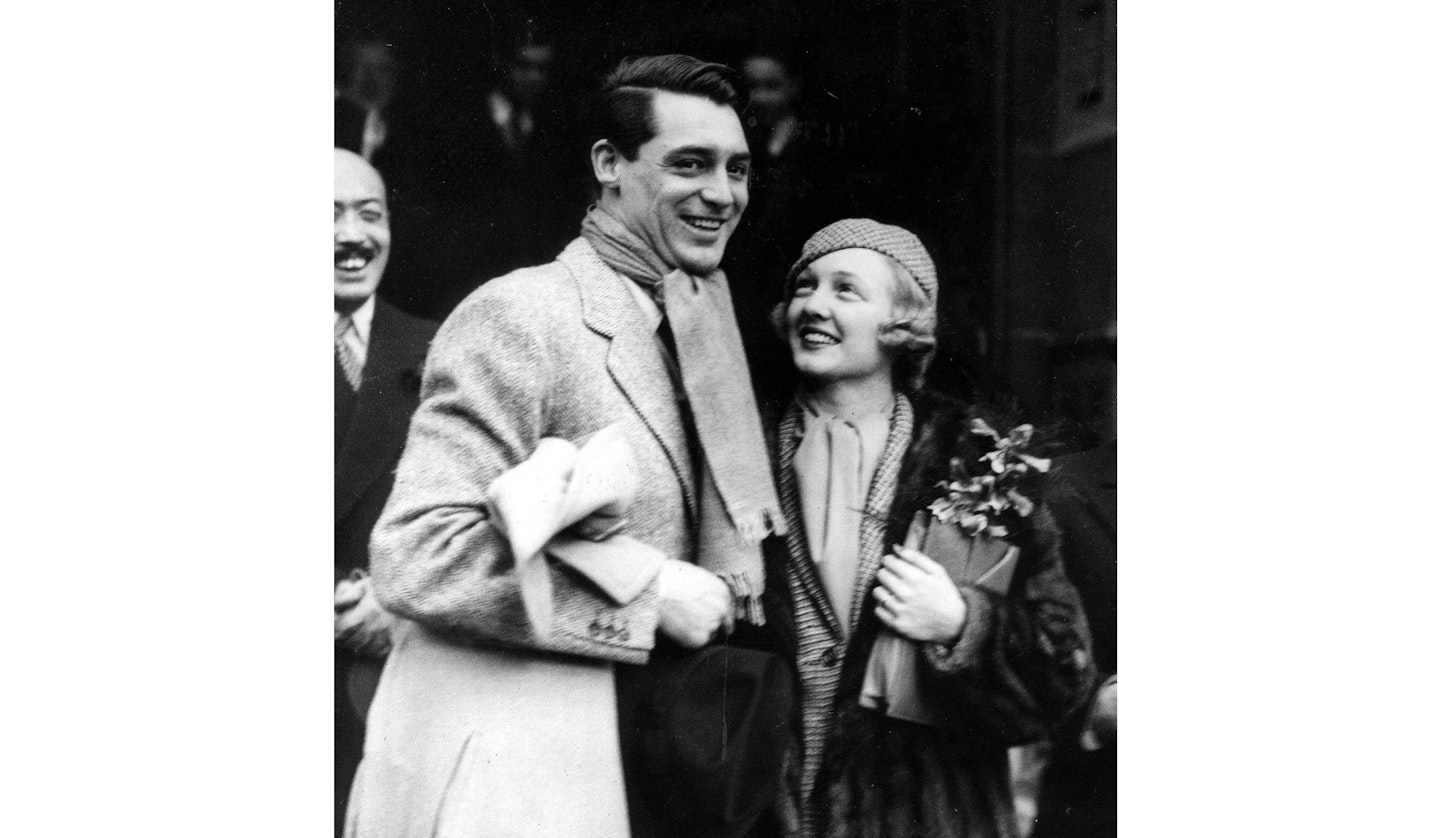

Grant’s first feature film was This Is The Night and before the end of 1932 his name appeared in the credits of six more films. He rented a house with another up-and-coming star, Randolph Scott – a perfect pair of glamorous Hollywood bachelors. But Grant’s bachelor days were numbered when he met Virginia Cherrill. The stunning blonde had appeared in Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights and at 25 she’d already been married twice. But the couple setting sail for England to get married – it was his first trip home in 13 years. The marriage didn’t last but Grant’s career went from strength to strength, making a total of 72 films and cementing himself in our hearts forever as the suave and sophisticated Hollywood star.

Did you know?

-

John Cleese character in A Fish Called Wanda is named Archie Leach in honour of Cary.

-

After believing her to be dead, Grant discovered his mother was still alive when he was 30 years old.

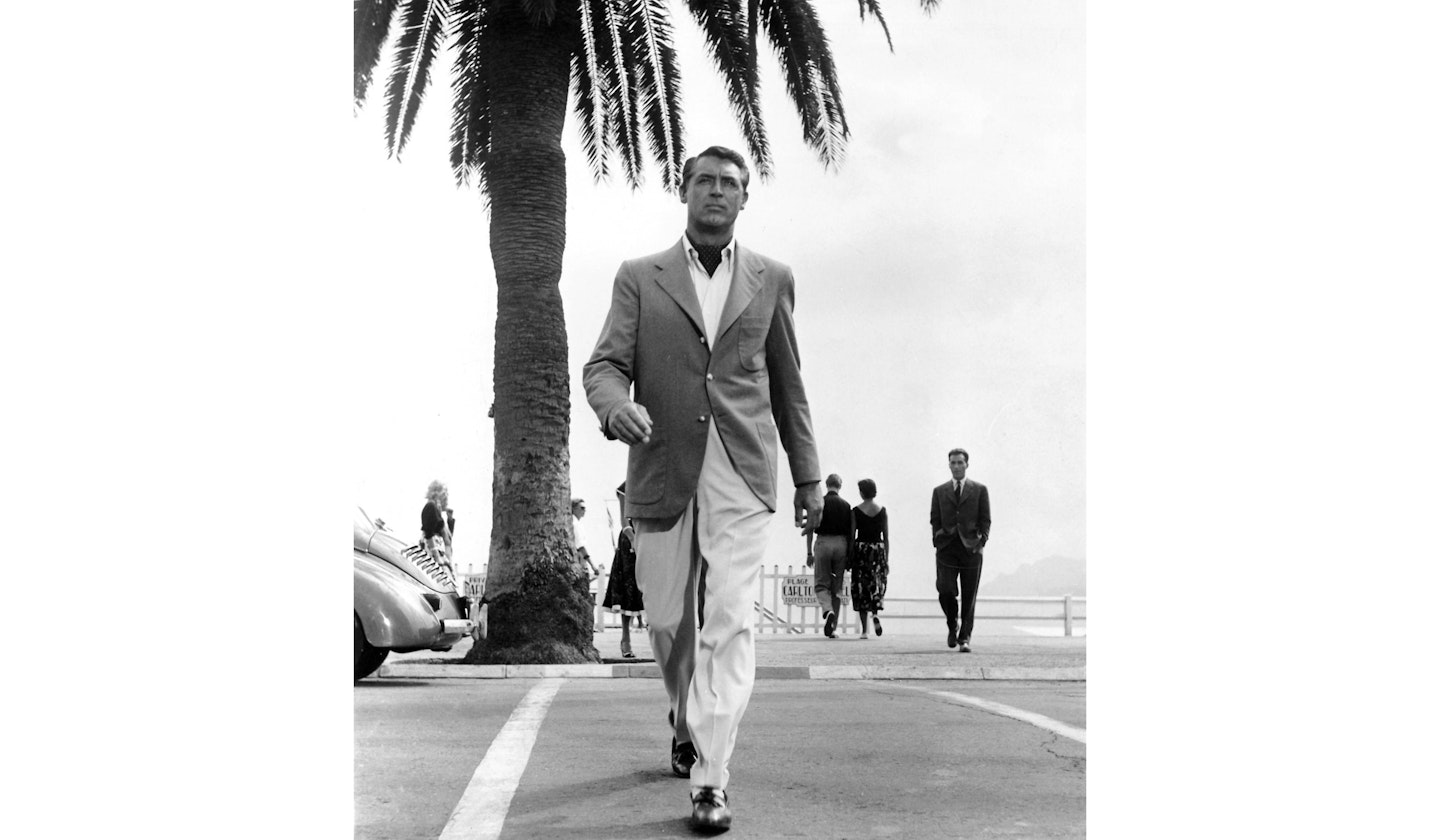

Cary Grant wasn’t just a movie star. For many people, he came to represent the living embodiment of male perfection. Men wanted to be him, women wanted to be with him. “Every man’s idol. Every woman’s dream,” was how director Stanley Donen saw him.

Then there was that voice. “Oh my God. He talks just like he does in the movies!” laughed a young Clint Eastwood on meeting him, early in his career. Although unmistakably British, Grant’s accent was unique. When Tony Curtis delivered a spot-on impersonation of him in Some Like It Hot (“I’ve got a funny sensation in my toes”), audiences needed no help whatsoever to help work out who he was doing.

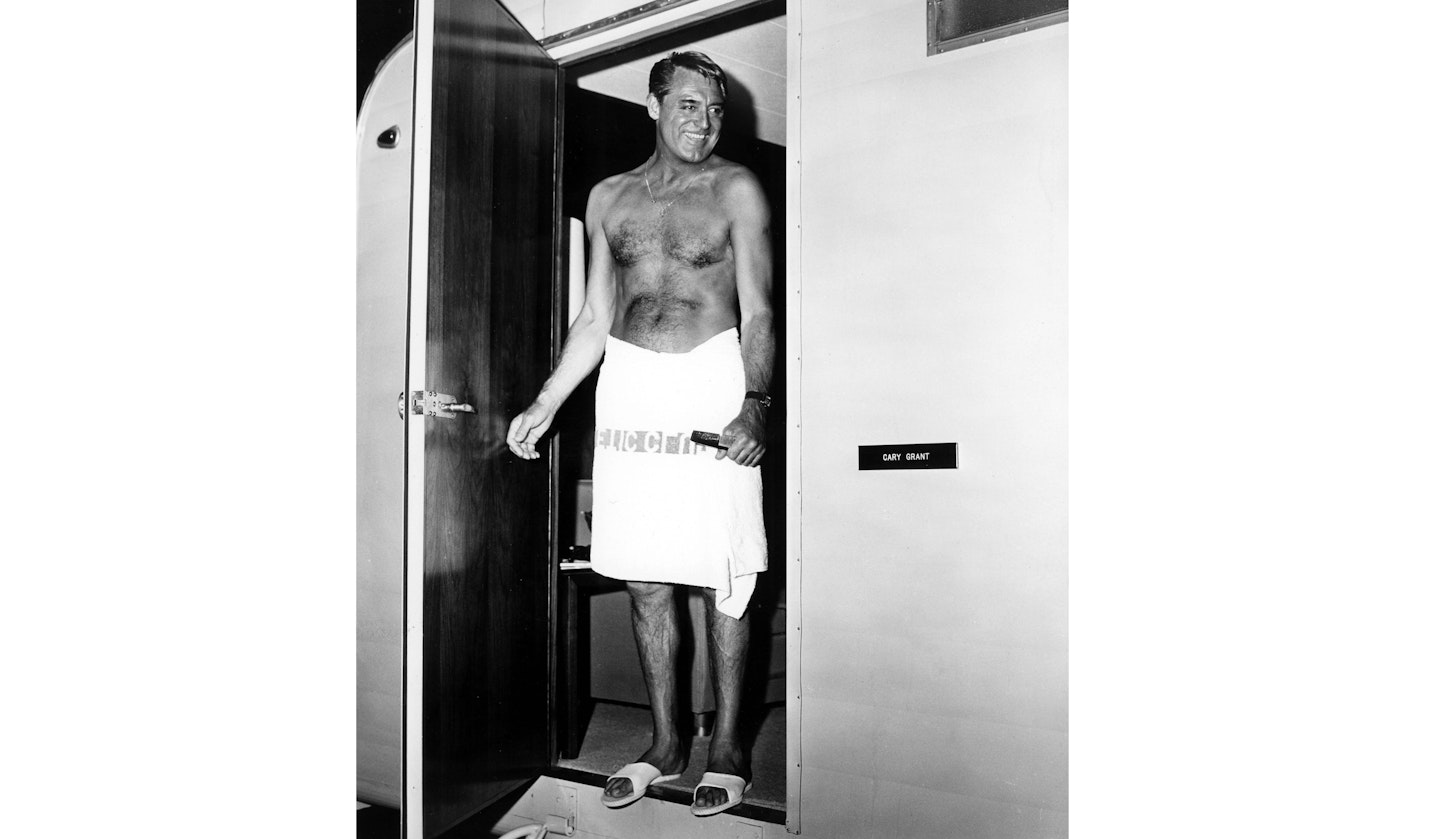

Always handsome, well-dressed, suntanned and debonair, maintaining his image took work. Grant was well aware he was to some extent acting both off screen as well as on. “Everybody wants to be Cary Grant. Hell, even I want to be Cary Grant,” he once said. “I guess to a certain extent, I did eventually become the characters I was playing. I played at being someone I wanted to be until I became that person. Or he became me.”

For 30 years, Grant appeared in more than 70 films including classics such as Bringing Up Baby (1938), His Girl Friday (1940), The Philadelphia Story (1940) and several outings with Hitchcock including Notorious (1946) and To Catch A Thief (1955). He rarely played the bad guy, in keeping with his generally clean image off-screen. In his first Hitchcock film, Suspicion (1941), audiences were so unhappy seeing him play a potential wife killer, the ending was changed, somewhat unbalancing the whole film.

For a long while, he didn’t even seem to age. The Cary Grant who performed opposite Audrey Hepburn in Charade (1963) did not look exactly the same as the man to whom Mae West said, “Why don't you come up some time, see me?” in She Done Him Wrong (1933). But he wasn’t far off.

Only in his final years, as his hair whitened and he began to wear glasses, did age betray him. “How old Cary Grant?” a rude journalist is once said to have asked in a telegram. His reply (whether true or not) is legendary: “Old Cary Grant fine. How you?”

He retired aged just 62, but he will remain immortal forever on our screens and in our hearts. As his biographer, Graham McCann puts it: “Cary Grant made men seem like a good idea.”

Iconic moment: On paper it doesn’t make a lot of sense. Why would a villain lure someone to a remote location only so they can be attacked by crop dusting plane? It doesn’t matter. Although hardly a typical Cary Grant scene, his pursuit in Hitchcock’s North By Northwest (1959) produced the most famous image of his career.

The real-life romances of Hollywood’s most eligible man Cary Grant

Few people have ever combined charm, wit and sophistication as effectively as Hollywood heartthrob, Cary Grant. Tall, dark, handsome and with a distinctive English accent which hinted at his humble origins in Edwardian Bristol, it is little wonder Grant charmed countless numbers of women both onscreen and off.

For 30 years, Grant appeared in more than 70 films, more often or not playing the guy who got the girl by the end of the final scene. But the reality for Grant was very different. He married five times, four of his marriages ending in divorce. Grant was suave and handsome and, by most accounts, thoroughly decent too. Why was he unable to achieve an enduring romantic relationship?

The real Cary Grant

In many ways, Cary Grant was surprisingly similar off screen to on. “Oh my God. He talks just like he does in the movies!” exclaimed a starstruck Clint Eastwood to the rest of the room on meeting him. Others report that the only real difference was that the genuine Cary Grant laughed far more in real life than he would ever have got away with on screen.

But who was “the real Cary Grant?” Cary had changed his name from the distinctly unglamorous ‘Archibald Leach’. “Archie just doesn’t sound right in America,” the studio told him. “It doesn’t sound particularly right in Britain either,” Grant admitted. Such name changes were not uncommon. But while never ashamed of his past, the working-class Bristol boy Archie Leach completely reinvented himself as suave and debonair Cary Grant.

The talk of the town

Grant emerged as a star in the Thirties at a time when the typical Hollywood man was a much tougher character. As Bob Hope joked: "A James Cagney love scene is one where he lets the other guy live."

Grant soon faced rumours that he was homosexual or at least bisexual. These rumours grew strengthened after Grant’s decision to live with fellow actor Randolph Scott, sharing a beach house in Malibu with him for 12 years. Grant seems less concerned about what was said about him than most, perhaps fanning the flames of gossip in the process. In later years, however, he spoke out: “If someone wants to say I am gay, what can I do? I think it’s probably been said about every man who’s been known to do well with women. I don’t let that sort of thing bother me. What is important, is that I know who I am,” adding later. “Now I don’t feel …(it’s)…an insult. But it’s all nonsense”.

Maybe it was. But Cary Grant had a dark secret in his past which would affect his relationships with women forever.

Mr Grant and Mrs Leach

Cary Grant’s mother had vanished when her was just nine years old. He had returned home from school to find her gone. His father, an alcoholic, told him his mother had taken a short holiday. Over time, the young boy came to realise the truth: his mother was never coming back. He later assumed his parents had simply split up.

Grant only learnt the truth more than 20 years later when his father died in 1935. His mother was still alive and his father had had her committed to a lunatic asylum. Grant, by now a rising Hollywood star in his 30s visited Britain and, finding his mother relatively well, moved her into a house in Bristol. Now effectively strangers, they enjoyed a slightly awkward relationship for the rest of her life.

Grant’s mother had always been eccentric. However, it seems likely his father had her institutionalised at least in part to free himself up to continue his relationship and ultimately start a second family with his mistress. The absence of a mother figure at such a crucial period in Grant’s life, must surely have impacted his future relationships with other women. Grant himself certainly thought so. “(I made) the mistake of thinking that each of wives was my mother, that there would never be a replacement once she had left.”

Virginia and Barbara

The news that his mother was still alive came soon after the failure of his first marriage to actress Virginia Cherrill. The beautiful actress was best known for playing a blind girl in Charlie Chaplin’s film, City Lights. “My possessiveness and fear of losing her brought about the very condition it feared: the loss of her,” Grant later said. The marriage lasted barely seven months.

Grant had been on the cusp of stardom in 1932. By the time of his second marriage to Barbara Hutton in 1942, he was a full-blown star. Hutton was an immensely rich woman, having inherited the Woolworth business fortune. Some dubbed the couple “Cash and Cary.” In fact, although it was not made public at the time, Grant had signed a prenuptial agreement which ruled him out from claiming any stake in her fortune, should they ever divorce as they, in fact, did in 1945. Grant disliked Hutton’s upper class “phony noble” friends and expensive dinner parties. They were essentially living in different worlds. Hutton ultimately married seven times and by the time of her death was close to bankruptcy. She did however say, “Cary Grant had no title and of my husbands, he is the one I loved most… he was so sweet, so gentle. It didn’t work out, but I loved him.”

New horizons

Cary Grant’s third marriage to actress Betsy Drake in 1949 led to some big changes in his life. He had announced he was quitting acting forever and soon after that, he was experimenting with drugs. Neither of these developments were to prove as dramatic as they sounded. Neither were also solely down to Betsy Drake although she certainly did exert a big influence on him at this point.

Grant’s ‘retirement’ from filming in fact proved very short-lived. But he was determined to make his third marriage work. Perhaps experiencing something a mid-life crisis as he entered his late-40s and 50s, he experimented with yoga, mysticism and LSD, then a drug legally sanctioned by the US government.

Grant took the hallucinogenic drug more than 100 times in the hope of enhancing his ability to connect with women. “LSD made me realise I was killing my mother through relationships with women. I was punishing them for what she had done to me,” he theorised.

For a while, he was a strong advocate of the drug claiming: “I learned to accept the responsibility for my own actions and to blame myself and no one else for circumstances of my own creating… At last I am close to happiness.”

In time, Grant came to feel, "taking LSD was an utterly foolish thing to do but I was a self-opinionated boor, hiding all kinds of layers and defences, hypocrisy and vanity. I had to get rid of them and wipe the slate clean."

It also did not save his third marriage. He and Betsy split up in 1958, divorcing in 1962. It was easily his longest marriage, at 13 years, but still some way off the enduring permanent relationship he sought.

Bringing Up Baby

In the mid-Sixties, Cary Grant really did quit the movie business for good. Although remarkably well preserved, Cary was getting older. But he had also “discovered more important things in life”. He had finally fulfilled a long-term ambition. At 62, he had become a father.

“She is my best production,” Grant said of his daughter Jennifer. "My life changed the day Jennifer was born… To leave something behind… That's what's important."

Grant proved a devoted father but sadly his marriage to Jennifer’s mother, actress Dyan Cannon, some 33 years his junior ended in a bitter and public court case in which Grant’s use of LSD was cited. As might be expected, Grant showed little concern for his own reputation or for pursuing any campaign against Dyan. His main abiding fear was the possibility of losing access to Jennifer. Happily, this didn’t happen.

He married just once more in 1981, choosing Barbara Harris, a British hotel public relations executive, some 47 years his junior as his bride. The two remained together until his death in 1986, aged 82.

Grant tended to be his own harshest critic where the failure of his marriages was concerned. Speaking after his third divorce, he said, “They all left me. I didn’t leave any of them. They all walked out on me. Maybe my marriages were all heavily influenced by something in my subconscious that’s related to my early years and the way I envisioned my mother… Maybe they just got bored.”

Whatever the truth, in this, he was definitely wrong. Too boring? Cary Grant was certainly never that.

Cary Grant's life is to be turned into a drama series

Cary Grant's life is to be depicted in a four-part TV drama, Archie. Written by award winning screenwriter, Jeff Pope, and starring Jason Isaacs in the leading role, the drama will be produced by ITV Studios and will premiere on its new and free streaming service, ITVX which launches later this year.

Speaking about his latest role, actor Jason Isaacs said, "There was only one Cary Grant and I'd never be foolish enough to try to step into his iconic shoes. Archie Leach, on the other hand, couldn't be further from the character he invented to save himself. Jeff's brilliant scripts bring to life his relentless struggle to escape the demons that plagued him, his obsessive need for control, his fears, his weaknesses, his loves and his losses. It's the story of a man, not a legend, and those are shoes I can’t wait to walk in."

Cary Grant’s relationship with Randolph Scott

He was Cary Grant, the handsome young British-born actor, a newcomer who would in due course become one of Hollywood’s most iconic figures. His friend was Randolph Scott, another tall Hollywood heartthrob in this case destined to become the star of many Hollywood westerns. The two men seem to have met on the set of Hot Saturday (1932), a drama which would see Cary’s debut as a leading man. Both hit it off immediately.

Their backgrounds could not have been much more different. Randolph had been born to a large, wealthy and generally supportive American family in Virginia in 1898. A keen sportsman, he served in the US Army during the First World War but had been generally expected to follow his father into a career in the textiles business. A trip to Europe changed his mind: young Randolph now wanted to act. His father – clearly an accommodating man - used his connections (notably Howard Hughes) to find his son a place in Hollywood. Randolph arrived in 1928, just as the movie business was reaching the end of the silent era.

Cary Grant had had none of these advantages. He had been born to poverty in Bristol, six years after Randolph in 1904 and had had an unhappy childhood. His father had been an alcoholic and his mother had mysteriously disappeared during the boy’s childhood. Cary had assumed she had walked out on the family and presumably died in the years since. By the time, he met Randolph Scott, he had achieved success on the vaudeville circuit, moved to Hollywood and, under studio insistence, changed his name from the distinctly unglamorous Archibald Leach to the much more palatable Cary Grant.

Although largely only a bit-part player up until that point, Randolph was nevertheless wealthier, more confident and better connected than the younger man when he met Cary Grant in 1932. He was undeniably a useful contact and introduced Cary to the man who had brought Randolph himself to Hollywood a few years earlier: Howard Hughes. In time, Hughes would become notorious as an eccentric recluse but in the Thirties, the young aviator and film tycoon was still a glamorous and powerful figure. Through Hughes, Cary and Randolph gained access to a whole new world of parties and wealthy and interesting friends.

This is not to suggest Cary was using Randolph, however: both men were signed up to Paramount and had bright futures ahead of them. There were a considerable number of British actors in Hollywood at this time: Ronald Colman, South African-born Basil Rathbone, Rex Harrison and David Niven, but Grant had only recently been Archibald Leach. But Grant’s humble background meant he probably felt socially inferior to all these men. Randolph was from a wealthy background, but it didn’t matter. He was American. The stifling old rules old social class didn’t apply in the US or least, not in the same way. In Hollywood, Cary Grant was free to re-invent himself.

In truth, no complex explanation is needed: the young actors’ friendship was perfectly genuine. But then they decided to move in together and the rumours started. They have never stopped.

In 1932, Cary Grant and Randolph Scott pooled their resources and shared an apartment in West Hollywood, moving into a more substantial residence a few months later. In 1932, Cary married to actress Virginia Cherrill and moved in with her in Havenhurst. Following their divorce in 1935, Cary rented with his friend again, this time sharing a beach house in Santa Monica. They continued to co-rent until 1942, when Cary married the heiress, Barbara Hutton. Both men had agreed, whoever re-married first would keep the house. In practice, however, Cary decided to move out when this happened and sold his share of the house to Randolph.

In truth, the decision to cohabit was not in itself that unusual: indeed, certainly at the beginning, it made sound financial sense. What is more surprising is that the two rising stars lived together for so long and through so many huge changes in their lives and careers. They also faced persistent and potentially career-damaging rumours that they were homosexual or more probably bisexual. It was claimed they were living together as lovers.

Despite this, they lived together for over a decade: longer than most Hollywood marriages endure. Cary Grant himself would ultimately marry five times during his life. Only his third marriage to Berry Drake (1949-62) would last longer than the period he spent living with the actor, Randolph Scott.

The rumours were not exactly dispelled by a magazine profile of the two men written by Ben Maddox in 1933. The profile was accompanied by a range of photos of Cary and ‘Randy’ enjoying a cosy domestic life together: standing side by side in the swimming pool, playing ball in a sun-soaked garden, exchanging glances over the dinner table, enjoying a sing song round the piano and generally doing what Americans call ‘making house’. These were more innocent times and the pictures probably looked less suggestive of what in the 21st century is sometimes called a ‘bromance’ then than they do now. That said, a picture of the stars wearing aprons in the kitchen, angered some people then in a way which they wouldn’t now.

It could also be argued, that the two men are clearly having a bit of fun during the photoshoot and that the images shouldn’t be taken too seriously. After all, had they actually been secretly homosexual, at that time a potentially very damaging accusation, they would presumably not have been so relaxed about the way the pictures of them might have been construed.

As it was, neither man’s careers seem to have suffered obviously as a result of the rumours. Ironically, Ben Maddox, who wrote the 1934 magazine profile was privately homosexual himself.

Paramount were keen to dispel any suggestion that the Cary Grant and Randolph Scott were homosexual. Despite the pictures, parts of Maddox’s profile were clearly designed to present a portrait of two girl-chasing bachelors.

“Need I add, that all the eligible (and a number of the ineligible) ladies-about-Hollywood are dying to be dated by these handsome lads?” Maddox wrote, before mentioning the cars the two men drove. “Oh-oh-oh, how the girls want to take a ride!”

Crude though this was, there was some truth in this. Cary and Randolph’s beach house became a famous party spot with the two stars playing host to their near neighbours David Niven and Errol Flynn. Other guests included Ginger Rogers, Noel Coward, Carole Lombard, Howard Hughes and Phyllis Brooks.

William Randolph Hearst Jnr remembered it as “a bachelor’s paradise…with girls running in and out of there like a subway station.” The two men also showed plenty of interest in women with both men marrying twice during the Thirties and Forties.

Why then, did the rumours persist?

“Cary will never know peace as long as his name spells news,” Randolph Scott once said of his friend. “I’ve seen him actually lose weight and sleep after reading certain items that touch upon his personal life.”

From the Thirties onwards, the character of Cary Grant has held a strong hold over the imagination of the world. Incredibly handsome, stylish, suave and debonair, Archibald Leach had reinvented himself as a new kind of film star, a world away from the tough guys who had traditionally dominated the male world of Hollywood until then. Add to this, some rumours about his having once lived with the openly gay fashion designer Orry-Kelly in the late Twenties and his years spent living with Randolph, then it is easy to see why he may have roused the unpleasant prejudices of Hollywood gossip columnists.

Cary may have also unwittingly provoked such people through the jealous guarding of his own privacy. “My personal affairs are none of your goddamned business,” he once bravely told the powerful columnist, Hedda Hopper. He also became curiously indifferent to attacks on his reputation. “If someone wants to say I am gay, what can I do?” he said in later life. “I think it’s probably been said about every man who’s been known to do well with women. I don’t let that sort of thing bother me. what is important, is that I know who I am,” adding later. “Now I don’t feel …(it’s)…an insult. But it’s all nonsense.”

Cary and Randolph enjoyed many ups and downs during their years living together. Although their first film together, Hot Saturday was a success, (“Randolph Scott is solidly virtuous as the boyhood sweetheart,” wrote a New York Times reviewer) they only appeared in one more movie together, My Favorite Wife (1940). Cary endured a rough patch in the mid-Thirties with both his first divorce and the shocking revelation in 1935 that his missing mother was not dead at all but had been secretly placed in a mental institution by his father 20 years earlier.

Randolph’s own first marriage to heiress Marion DuPont ended after four years in 1939. He married a much younger actress, Patricia Stillman in 1944. They would remain married until his death more than 40 years later.

He and Cary never lived together again. By the end of the Thirties, Cary Grant was fast becoming established as one of the greatest Hollywood stars there has ever been. Randolph Scott would never achieve this status himself but as a leading figure in the hugely popular western genre, would become a major star in his own right especially from the late-Forties onwards. He retired soon after one of his biggest successes, Ride The High Country (1962). The success of his second marriage and his tough guy image on screen (in reality, not really proof of anything) probably led to a decline in speculation as to his sexuality. For Cary Grant, ultimately divorced four times, the speculation continued with one biography claiming to ‘out’ him soon after his death.

We will never know for sure whether Cary Grant and Randolph Scott were ever secretly lovers or not. Perhaps it doesn’t matter. But three things will always be certain. Both men were great actors. Both remained friends until the end of their lives. And both men died within 100 days of each other: Cary Grant, aged 82 in November 1986, Randolph Scott, aged 89 in March 1987.

Yours Retro magazine is all the latest classic film, music and nostalgia you need, read more here.